(The first in a series of blog posts explaining why, and how, we are adding Box as a cloud service in addition to our long-standing integration with Google Drive.)

When we first started working on Kerika, back in 2010, Google Docs was an obvious choice for us to integrate with: it was pretty much the only browser-based office suite available (Microsoft Office 365 wasn’t around and Zoho was, and remains, somewhat obscure), and we were quite sure we didn’t want to get in the business of storing people’s desktop files in the cloud.

Google Docs (not yet renamed Google Drive) did have various limitations in terms of the file types it would support, and further limitations on the maximum size permitted of different types of files — the largest spreadsheet that they would support, for example, wasn’t the same size as the largest Word document — but the idea of building Kerika as a pure-browser app was a very appealing one.

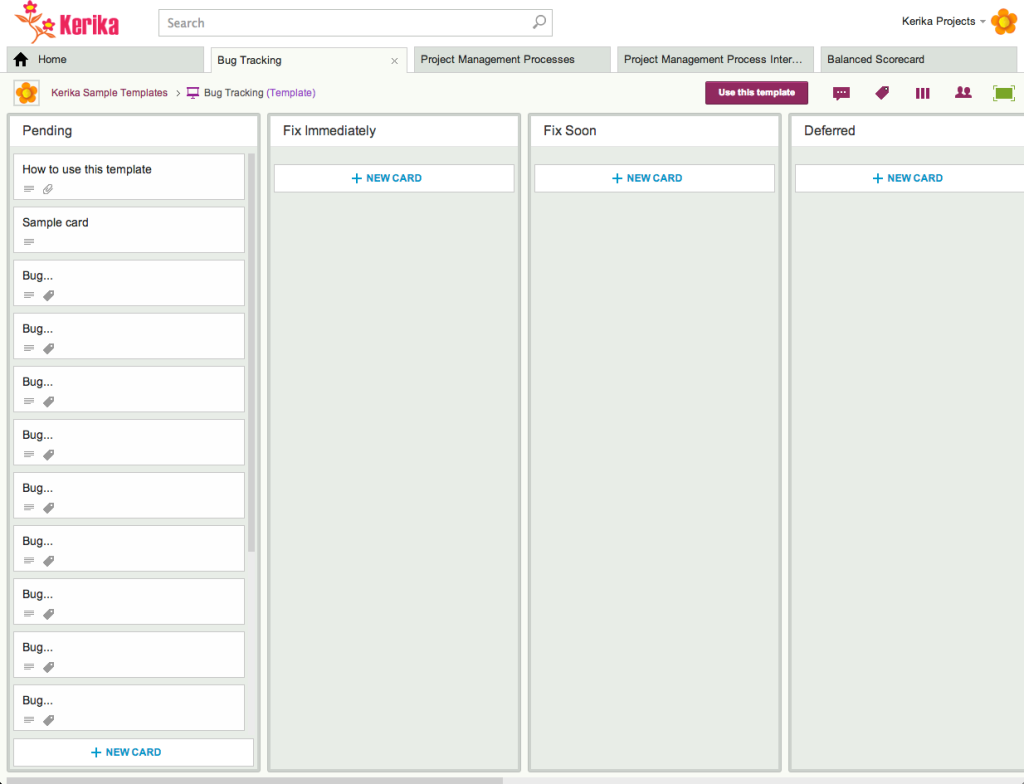

So we integrated with Google Docs at a low level, fully embracing their API, to provide a seamless experience unlike anything that you might find from competing products:

- When you add a document to a card or canvas in a Kerika board, it is automatically uploaded to your Google Drive, where it is stored in a set of nested folders.

- When you add people to a Kerika board, their Google Drives automatically get dynamic links to your Google Drive, giving them just the right access, to just the right files.

- When people’s roles change on a project team, their Google Docs access is automatically and instantly changed.

- When a document is renamed in Kerika, the new name is reflected back in Google Drive.

Many of our users who are already using Google Docs loved our integration: one user went so far as to say “Kerika makes Google Docs sing!”

The Google integration was not easy, particularly in the early days when there were wide gaps between the documentation and the reality of the API: we had to frequently resort to the wonderful Seattle Tech Startups mailing list to cast about for help.

But it seemed worth while: our Google integration has definitely helped us get paying customers — organizations moving off the traditional Microsoft Office/Exchange/SharePoint/Project stack were looking for a tool just like Kerika, particularly if they were also grappling with the challenges of becoming a Lean/Agile organization and managing an increasingly distributed workforce.

We even signed up organizations, like the Washington State Auditor’s Office who started using Google Apps for Government just because they wanted to use Kerika!

But, there are other folks we encounter all the time who say to us: “We love everything about Kerika except for the Google integration”

Some folks want to work with Microsoft Office file format all the time (although that’s possible even with our Google Drive integration, by setting a personal preference, and will be even easier in the future with new edit functions announced at Google I/O), but, more commonly, we came up against a more basic concern — people simply distrusted Google on privacy grounds.

It’s debatable as to whether it’s a well-grounded fear or not, but it is certainly a widespread fear, and it is not showing any signs of diminishing as we continue to talk to our users and prospects.

Some of this is due to a lack of understanding: users frequently confuse “security” and “privacy”, and tell us that they don’t want to use Google Apps because it isn’t secure. This is really far off the mark, for anyone who knows how Google operates, and understands the difference between security and privacy.

Google is very secure: more secure than any enterprise is likely to be on its own. They have a lot of software and a lot of people constantly looking for and successfully thwarting attackers. It’s always possible for someone to hack into your Google account, but it will be through carelessness or incompetence on your end, rather than a failure on Google’s part.

Privacy, however, is a different matter altogether, and here Google does itself no favors:

- It’s Terms of Use are confusing: their general terms of use, for all Google services, contains this gem which drives lawyers crazy: “When you upload, submit, store, send or receive content to or through our Services, you give Google (and those we work with) a worldwide license to use, host, store, reproduce, modify, create derivative works (such as those resulting from translations, adaptations or other changes we make so that your content works better with our Services), communicate, publish, publicly perform, publicly display and distribute such content.”

The Google Apps for Business Terms are much more specific: “this Agreement does not grant either party any rights, implied or otherwise, to the other’s content or any of the other’s intellectual property.”

But most people derive a first, and lasting, impression from Google general terms, and few get around to investigating the GAB specific terms. - Google finds it hard to acknowledge people’s privacy concerns. This is somewhat puzzling, and can perhaps be best explained as a cultural problem. Google genuinely thinks itself of a company that “does no evil”, and therefore finds itself reflexively offended when people question its commitment to privacy. It’s hard to address a problem that challenges your self-identity: the Ego acts to protect the Id.

Entire sectors seem closed to Google Drive: lawyers, who could certainly benefit from Kerika’s workflow management, and healthcare, which is already adopting Lean techniques (pioneered locally by the Virginia Mason hospitals.)

In the small-medium business (SMB) market in particular, there isn’t any meaningful outreach by Google to address the privacy/security concern. (Google does reach out to large enterprises, but in the SMB market it relies entirely on resellers.)

For our part, we have done a ton of work persuading people that it’s OK to use Google Drive, but we don’t get paid for this (we are not a Google Apps reseller), and this is, at best, a distraction from our core mission of building the very best work management software for distributed, lean and agile teams.

We need an alternative cloud storage platform: one that has robust capabilities, is enterprise-friendly, and doesn’t come with any privacy baggage.

The full series:

- Part One: Privacy Overhang

- Part Two: Transparency

- Part Three: Considering Alternatives

- Part Four: The Dropbox Option

- Part Five: The OneDrive Option

- Part Six: The Box Option

- Part Seven: Disentangling from Google

- Part Eight: Our experience with Box (so far)

- Part Nine: Final QA