Many, many years ago, as a young boy living in Delhi I had the good fortune of being a neighbor and friend to the then-elderly, since deceased, M. Chalapathi Rau, the publisher and editor of the newspaper National Herald which had been founded by Jawarharlal Nehru himself during India’s freedom struggle. (“M.C” or “Magnus” as he was known to his friends was a man of many talents and a true eminence grise who unobtrusively operated the levers of power in India.)

To help me research a school project, M.C. took me to his newspaper’s printing press, a vast, clanking space where I watched with great fascination the painstaking process of laying out moveable type by hand: a craftsman’s job that had remained essentially unchanged, at least in India, since the 19th century. I did my school project, thinking that this would be my first and last experience with typesetting…

At college, however, typesetting reappeared: in order to get a job, one had to have a beautifully laid out resume, particularly if one had no “professional experience” to list other than the insalubrious qualification of having toiled in the scullery of a campus dining hall for minimum wage. So, I dutifully learned the obscure commands that helped set fonts and margins using troff, the first document preparation software for Unix computers.

I prepared and padded my resume, bluffed my way into my first job, and assumed that that would be my last encounter with typesetting. Ironically, my first job was at AT&T Bell Labs, working on Unix-based applications.

Typesetting is closely tied to the history of Unix, and, indeed, provided the raison d’etre for Unix’s existence. In 1971, when Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie (and others) at Bell Labs wanted to get funding for developing the Unix operating system, their business case was based upon the rather tenuous argument that developing this new operating system (Unix) would help them develop a better typesetting program (troff), which could be used by Bell Labs to file patents.

In those halcyon days, Bell Labs generously recognized and encouraged geniuses to explore their ideas, and, more mundanely, Bell Labs actually did need a better typesetting programs: since it’s inception in 1925 the organization had averaged one patent per business day (and collected about nine Nobel Prizes by the time I showed up as a very junior programmer).

So troff, the typesetting program, is responsible for the creation of Unix, which means that typesetting is the reason why Linux, cloud computing, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc. all exist today!

Typesetting occupied a relatively small part of my workday until I started moving into management roles, which coincided with the widespread adoption of Microsoft’s Word software. Suddenly, most of my day was spent typesetting memos, performance appraisals, proposals, etc. I emphasize “typesetting”, rather than “writing”, because Microsoft Word remains, at heart, a typesetting program, not a writing program. It requires you to learn the same obscure catechism of tab settings, kerns and serifs, character and line spacings that those ancient typesetters at the National Herald had mastered as a craft.

And, yet, no one considers it strange that all of us highly trained, highly paid “knowledge workers” are required to master a craft that was first invented in China in 1040 AD!

The advent of the modern Web, starting with the release of the Netscape browser in 1995, has provided little relief: we exchanged one set of obscure keystroke combinations for another, equally opaque set of symbols (i.e. HTML). It is only in recent years that blogging tools, like the excellent WordPress software I use to pen this essay, has helped hide the typesetting and allow users to focus on the writing.

Between the release of the Netscape browser and the current robustness of WordPress came the advent of Google Docs. Google Docs’ primary innovation (or, more precisely, Writely’s primary innovation — remember Writely?) was to offer online editing; Google Docs did nothing to fundamentally alter the typesetting nature of word processing.

Google Docs continues to evolve, but as a persistent shadow of Microsoft Office. This makes sense from a business perspective, of course: it is easier for Google to get customers signed up if they can state simply that Google Docs works like the familiar Microsoft Office, and is a lot cheaper and easier to access. It would be much harder to get people to sign up for a Google Docs that seemed to fundamentally alien in comparison to that reliable reference, Microsoft Office.

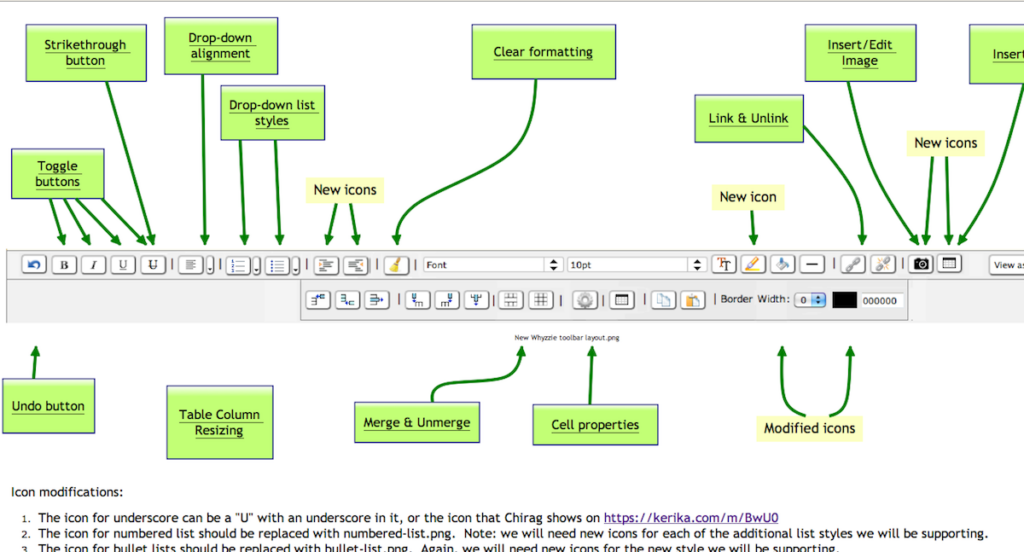

And, so it continues… Centuries after the invention of moveable type, we remain trapped in its formatting conventions. At Kerika, we are starting to think seriously about making our embedded text editor (which is based upon Whizzywig) be the primary way for people to write for the Web. Kerika is all about creating and sharing pages stuffed with your greatest ideas and coolest content, and it’s high time we put aside typesetting. For good.